The Banjer 37

Banjer 37's History / Technicals

1.- History

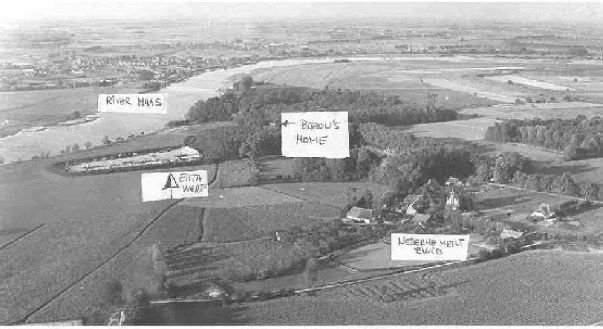

In 1959 the rowing-boat of Maurits Baron van Wassenaer was stolen. He decided to build a new one. This was the start of one of the most succesful shipyards in the Netherlands: Eista Werf in Ammerzoden, close to Netherhemert. In the timeframe between 1960 and 1980 more than 4.500 rowing-boats, and 2.500 Doerak motorboats were build in steel, as well as some other yachts like Arthur Nova, Sesam, etc., also in steel. During the same period many polyester motorsailers left the shipyard, like 95 Banjers, around 100 Roggers and around 100 Krammers. The designer of all these yachts was the very succesful Dick Lefeber.

After having made 2.500 Doeraks in steel, for the Netherlands inland waters, van Wassenaer decided to build a prototype GRP boat as a seagoing motor-sailer. His designer Dick Lefeber had extensive experience of fishing boats design, hence the very traditional Banjer's hull shape. The yard Eista Werf made the wooden plug, Banjer 1, then had Banjer 2 moulded and fitted out to exhibit at the Amsterdam Boat Show, about 1968.

THE DESIGNER: DICK LEFEBER

Dick Lefeber’s designs are characterized by their attractive, timeless lines, functionality and space.

He started out as a draughtsman/designer with an inland boatyard, where he designed flat-bottomed vletten (classic Dutch motor cruisers), tugs, inland vessels and fishing cutters.

It was in the 60s and 70s, when Dick Lefeber worked for ‘Eista Werf’, that he really won his spurs by designing the popular Doerak and Marak models. He also drafted the well-known Rogger, Banjer and Krammer designs. In that period he developed at least 40 models and variants in steel and polyester. He went on to design countless Lemster Aken and Staverse Kotters for ‘traditional’ builders.

Dick Lefeber

Click on image to know more (Dutch)

|

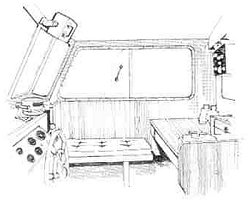

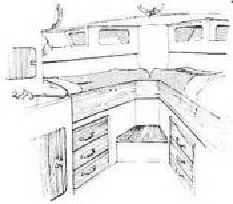

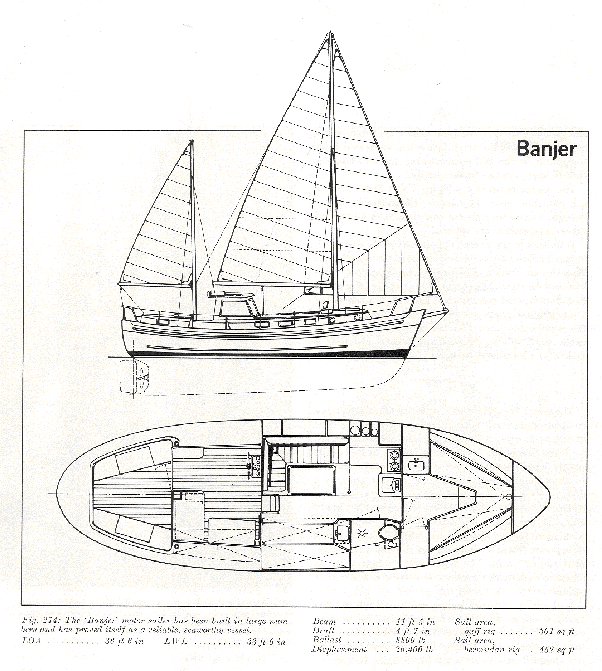

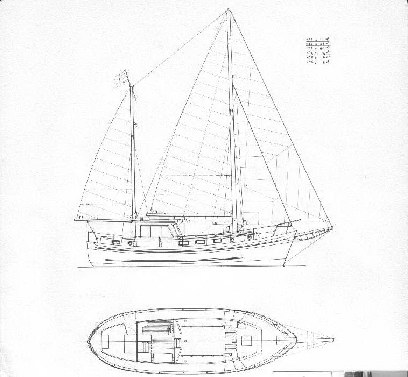

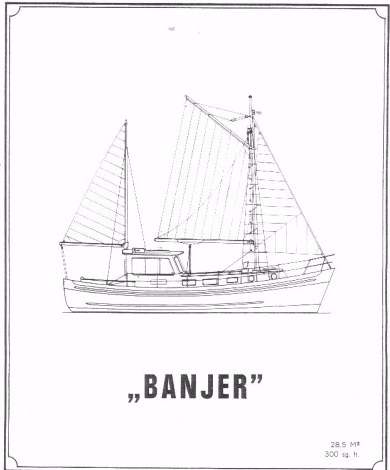

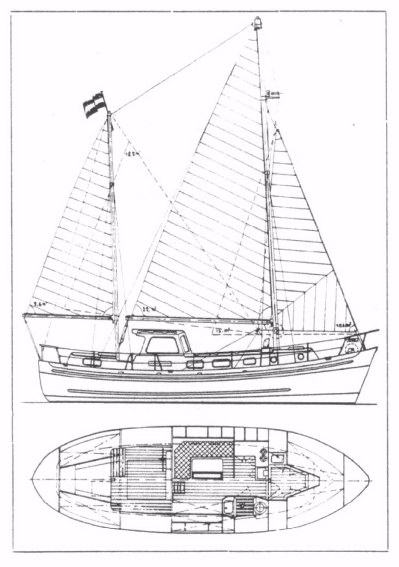

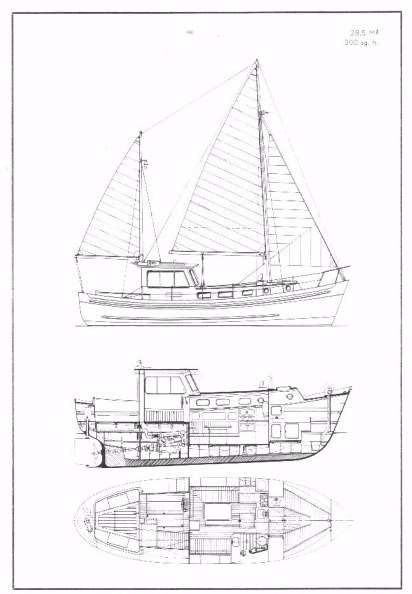

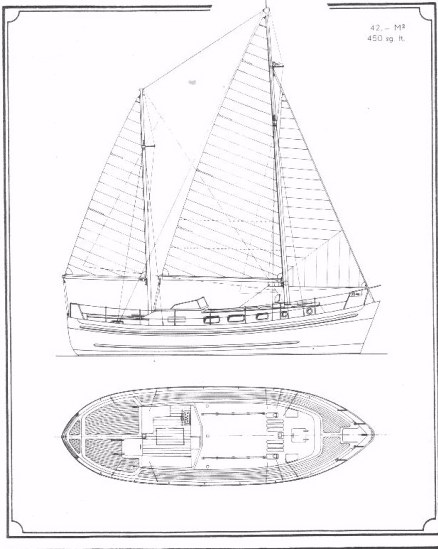

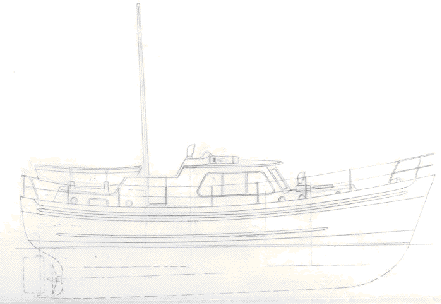

A couple of Dick Lefeber's Banjer drawings

Alec Ingle, went to the show and bought Banjer 2 off the stand. Van Wassenaer asked him if he knew of anyone to sell the boats in UK, and as Alec had just retired from the RAF he agreed to act as agent. He started Stangate Marine (named after Stangate Creek off the Medway where he sailed), and the sales were quite sucessful, so in 1972 he bought the shipyard at Littlehampton as a sales base.

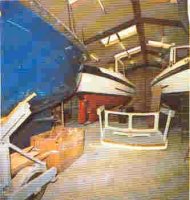

The 35' Rogger followed quite quickly and was very successful. Nephew Mike joined Alec in business in 1974. By this time the currency had gone wrong so van Wassenaer and the Ingles made the decision to move production to UK, and started with the largest of the Roggers range, the 14m Atlas. Eventually all production moved to UK, using Halmatic as the hull moulders.

They closed the yard in 1979 when inflation made it impossible to build at a profit, and the moulds were dispersed to two or three different places. It looked like if Banjer's were broken up, although now it seems that they are now in Berlin, Germany.

Eista plaquette.

Eista Werf's place

Stangate Marine premises at Littlehampton (circa 1973)

Find the full Eista boats' history at:

Pages kept by Eista studious, Frank Korneef

(Click on image to go)

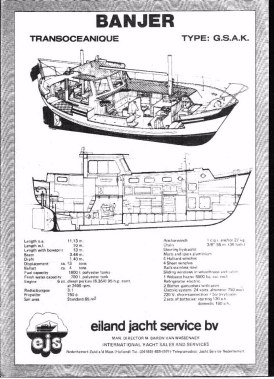

2.- Banjer's basic data.

Banjer 37 Motorsailer

LOA

|

36 ft 6 in

|

11,13 m

|

LWL

|

33 ft 6 in

|

10,21 m

|

Beam

|

11 ft 5 in

|

3,48 m

|

Draft

|

4 ft 7 in

|

1,40 m

|

Ballast

|

8.800 lb

|

4 Tm

|

Displacement

|

26.400 lb

|

12 Tm

|

Sail area (Gaff rig & small bermudan rig)

|

301 sq ft

|

28 m2

|

Sail area (Large bermudan rig, no bowsprit)

|

452 sq ft

|

42 m2

|

Sail area (Transoceanique version )

|

807 sq ft

|

75 m2

|

Sail area (Trans. version A. Gérard Borg)

|

667 sq ft

|

62 m2

|

Sail area (Trans. version B. Gérad Borg)

|

1.000 sq ft

|

97 m2

|

3.- General Description/Construction

Banjer 37 Motorsailer is a handsome g.r.p. ketch rigged motorsailer, modeled on the lines of a North Sea trawler, with a distinct emphasis on the motoring side of her job. Banjer 37 was built to Lloyd's specification. The hull and superstructure were molded by Polyboats of Amsterdam and the minimum hull thickness is half of an inch.

Hull, decks, superstructure, cockpit, forecabin and toilet/shower compartment are in GRP. Longitudinal and transverse bulkheads ar of marine plywood. Fuel tanks (350 gall.), Fresh water tanks ( 150 gall) and waste tank (20 gall.) are all in fiberglass, as well as the rudder. Rudder head and heel are made of stainless steel. All exterior wood is in teak and the interior woodwork of marine plywood and teak. Cabin soles are also in solid in teak.

The G.R.P. hull was moulded in two halves, and the part modulus then bolted and the halves laminated together. The 4 ton ballast goes in the form of cast iron pigs laid in the trough-shaped keel, and the whole is then cemented in and glassed over.

There was a choice of three sail plans: 1) a 300 sq ft version with a gaff rigged mainsail, and a comparatively short main mast. 2) a similar sized rig, with a bermudan mainsail, and 3) a somewhat larger bermudan rig, with a total of 450 sq ft, and the opportunity to set mizzen staysails, if required. For motoring, the jib and mizzen were just enough to act as standying sails for those who would use the boat primarily as a motorboat, but except in fresh winds the main as well would be needed to really quieten the motion.

To improve the sailing abbilities of the Banjer, in a search for the "Perfect Motorsailer", Gérad Borg and architect Pierre Jollois studied various possibilities, and finally designed a 62 m2 and a 97 m2 sail plans, including " foc, trinquette, grand'voile, voile d'étai et artimon", so deriving the 'Transoceanique' version. The biggest sail, the genoa, doesn't exceed 43m², to keep things handable by short crews.

The Eista-agent for England, Stangate Marine, built this Banjer 'Transoceanique', with a 2.13 mts. bowsprit and a standard sailplan of 75 m2, from about 1976, after the production had stopped in Holland. Just like the Rogger-series, building in England was much more 'low cost' than producing in the Netherlands.

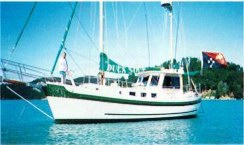

Banjer 37 is highly suitable for extended coastal cruising and also proved her sailability through long passages. We can find Banjer 37 motorsailers as far from her original home waters as in Papua New Guinea.

4.- Lines/Sailing

Banjers' lines are those of a true motorsailer, so they have a hull that performs efficiently under power. Bred from North Sea trawlers, Banjers were conceived basically as seagoing motor boats, with a big propeller and auxiliary sails. Also, the relatively small draft was very convenient for their use in The Netherlands and central Europe's sailing grounds, plenty with navigable canals and shoal drafts. Hence the abating masts. At a seaway, the natural tendency to roll of such a design was evident: Sails were needed to dampen down motion at most points of wind and seas conditions.

Later, taller mainmasts and bowsprits were added, to allow for a better performance under sail alone, so deriving the "Transoceanique" versions, that seem also to carry a heavier ballast. This proved to be a significant upgrade, not only improving Banjer sailing abilities, but also dampening rolling down more efficiently, because of the higher inertia of rig and sails, and the higher force of wind on the bigger sails.

With her ketch rig and bowsprit (when fitted), Banjers allow for the proper combination of sails for every sea and wind condition. Reaching in a breeze with full cloths is what they like the most, being able to attain respectable speeds in spite of their heavy displacement. Some Banjers even display also a mizzen satysail, that gives extra power when the wind is more gentle.

The good performing under motor and sail to windward, in conjunction with the big, of good visibility and well protected pilothouse (most of the versions), makes for a fast and pleasant headwind motorsailing, conditions in which sailing boats with exposed cockpits may force their crew to wear their oilies and suffer constant spray. In a Banjer you can sit at the helman's position enjoying a glass of wine (or a pink gin!) in your favourite shirt, while comfortably and effectively beating to windward, with the right combination of sail and engine power, in a full force 6 over a choppy sea. So here we have the real Motorsailer philosophy, in line with other North and Central Europe designs, such as Nauticats, Fishers, Roggers, LM's, etc.

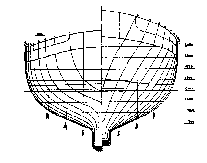

Transversal sections

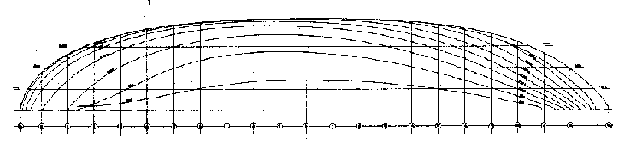

Vertical proyection

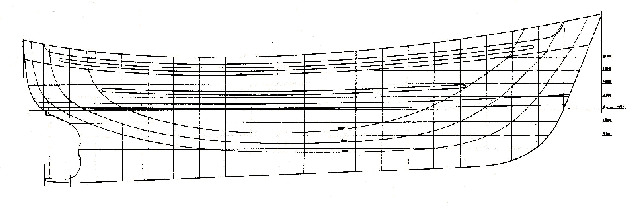

Lateral proyection

5.- Propulsion and helming.

The engine, originally either a Perkins 4 cylinder diesel delivering a continuous 62 BHP or a Perkins 6 -cyl delivering 95 BHP, is very accessible from the wheel house and provides ample power for the boat. The reduction gear was originally a Paragon, hidraulically actuated, with a 3:1 ratio. The 28 or 30 inch three bladed propeller, gives excellent handling and power through a headwind.

Going to winward even in a 4-5 wind conditions, the hydraulically operated helm, once set, will maintain course for some minutes before a check becomes necessary. Governing backwards, as to enter a narrow berth, is not very effective, due to the long keel and poorest rudder performance, but the power of the tandem engine-propeller, helps in the task. In calm conditions she can turn 360º within one boat length with the only use of ahead-astern power and working the helm accordingly. Anyhow it is strongly advisable to install a bow thruster to handle her backwards in a efficient and tidy manner.

The diameter of the turning circle at full speed is two and a half boat lengths (31 seconds) and starting from rest is two boat lengths (37 seconds). From full ahead to full astern the boat remains under full control and from full ahead to all way of vessel, it takes less than one boat length. (Data taken from Eista Werf's sailing tests)

6.- Accomodation/Layout

Accommodation was possible in two basic versions, one of them with four variations:

1.- Rear Cabin

1.2.- Central cockpit

1.2.2.- Open cockpit, windshield. (Type A-3)

2.- Rear Cockpit, closed wheelhouse (Type A-4)

Two of them are illustrated in the figure below. At the top we can see the rear cabin and centre-cockpit version, with a small wheel house (A-2), whereas the accommodation plan shows the after-cockpit layout, with a larger wheel house (A-4), which is the layout version of the two boats displayed below (One of them with a transoceanique rig and the other with large bermudan rig, no bowsprit)

Duck Soup

|

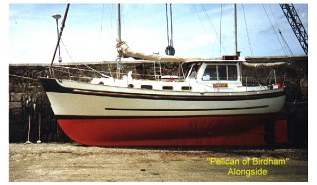

Pelican of Birdham

|

|

|

At the rear cockpit version, entrance to the wheelhouse is from the cockpit through a sliding door, with a high sill, on the port side. The wheel and the instruments console is to port. A compass is fitted at the front of the wheel. Visibility from the helm is excellent, but if the helmsman needs to communicate with deck crew forwards, it becomes necessary to open the central window. There is a bench for two to starboard and behind this is the chart table, with ample provision for electronics on the bulkhead. A bunk lies beneath this bench, but it is not very usable, except for storage purposes.

The companionway is well provided with teak handles down into the main saloon. Here the expanses of teak panelling have been balanced by the use of antique brass hinges on doors and cupboards. There is a settee-berth to port which can convert into a double bunk. There is another bunk which can be pulled out from under the starboard settee, and there is another bunk over this.

A waist-high partition separates the table from the galley, which is very pleasant to cook in. Facing this to starboard is the toilet, finished completely in white, with a sea WC, a stainless steel basin and hot and cold water from the heater in the galley. With ventilation and full headroom this sealed compartment contains also a shower.

The saloon is rather small considering it is the living area for a 37 ft boat, but it does contain a great deal of storage space. The fresh water tanks are moulded into the hull beneath the forward quarters and the saloon. Fuel tanks are located by the sides of the engine compartment.

The pleasantly forward cabin is fitted with two bunks, that can convert into a huge bed, shelves and lockers, a wardrobe and a stainless steel basin. The forepeak houses 30 fathoms of 3/8 inch. chain.

Waste and bilge water were originally cleared by one of the two Whale Gusher pumps, one in the toilet serving the two forward watertight compartments and the pump in the rear locker serving for the engine and stern sections.

At the rear cabin version the cockpit is substituted by a nice cabin with two bunks, making this version an ideal for a two couples cruising, although you sacrifice the possibility of lunching/partying outdoors.

7.- Rigs

As told before there was a choice of three sail plans: 1) a 300 sq ft version with a gaff rigged mainsail, and a comparatively short main mast. 2) a similar sized rig, with a bermudan mainsail, and 3) a somewhat larger bermudan rig, with a total of 450 sq ft, and the opportunity to set mizzen staysails, if required. For motoring, the jib and mizzen are just enough to act as standying sails for those who would use the boat primarily as a motorboat, but except in fresh winds the main as well would be needed to really quieten the motion.

From circa 1974 a more sail oriented conception was developed, in the pursuit of a 50/50 motorsailer, and taller masts and big bowsprits were added, so creating the Transoceanique (or Transoceanic) rigs, with a 2 m bowsprit, an up to 11.9 m tall main mast (from cabin roof), and 65, 69, 75, 80 or even 97 sq. m. sail areas, depending on configuration, with or without mizzen staysail, etc. This rigs, due to the bigger masts and sails, perform much better than the short rigs, both in terms of sailing under wind power and softenness of the motion. Ballast was increased from 4 to 5 tonnes (In units with the bigger sail areas) and fuel carrying capacity was also increased from 700 lt and 900lt, depending on previous versions, going up to 1600 lt.

Transoceanique version units were made in Stangate, hulls number 70 and above. Some earlier Banjers are now said to be Transoceanique (Or Transoceanic), but in fact are other versions, which's owners have increased the sailing area.

Drawings of versions and rigs configurations:

In first place, you can see plans and views of the Transoceanique version, with a rear cabin and long wheelhouse (Type A-1), like KITTY BOOT's. Other Banjer, DUCK SOUP, as you could see upwards in this page, is also a Transoceanique version, but with a rear cockpit (Type A-4).

Now we have a totally different rig, away from the transoceanique: One of the originals, with short main mast, gaffer rig and a 28,5 m2 sail plan. It is the version of the trial model BANJER, you can see at our Home page, and also VROUWE KLAZINA's.

In the drawing below you can find the A-2 version with an open wheelhouse and a rear cabin, with a tall bermudan rig and 42 sq. mts. sails, which is the version of TAPIR, although this boat now performs a bowsprit. PELICAN OF BIRDHAM, you can see upwards in this page, has the same rig, but a closed wheelhouse and a rear cockpit (A-4).

Down here, we find now another of the initial versions, a A-4 rear cockpit with a 28,5 m2 sail plan, but a bermudan one, in this case. This is the rig of ROBBE, you can find within these pages and also MARIE's version, although in this case a later bowsprit was added.

And, at last but no least, down here the A-3 "Mediterranée" version with a center open cockpit with windshield and a rear cabin, performing a large bermudan rig, with a 42 m2 sailplan. This is the version of KITTYHAWK although a bowsprit seems has been added latly.

Our friend and Eista site master, Frank Koorneef, sent us this drawing from a never built version: A Banjer Motorboat (Named SUPER BANJER), coming directly from Dick Lefeber's drawing board thanks to his charming widow.

With the passing of time many Banjers have come through several changes, the most popular having been the addition of a bowsprit and/or bigger masts, to increase sail area and so improving the performance under sail. You'll find through this site's pages many good examples of those changes.

ANATOMIE DU BATEAU IDEAL

(By GÉRARD BORG)

Extracted from the book EISTA BANJER GUIDE, by Gérard Borg. Gérard was helped by Pierre Jollois, the developer of the Transoceanique version for the french market, as far as we know.

POURQUOI UN AUTHENTIQUE ET PUR VOILIER ?

En matière de bateaux de croisière deux faits, entre autres, sont surprenants : l'intolérance dogmatique des uns et l'énormité des erreurs commises par les autres.

On imagine mal à quel point aujourd'hui le choix d'un bateau précède la connaissance des bateaux et la fréquentation de la mer.

En ce qui concerne plus spécialement le fifty, on a dit parfois qu'il était un médiocre voilier et un piètre bateau à moteur.

C'était probablement vrai jusqu'à présent pour la majorité des fifty. Comme il est, également vrai que de nombreux voiliers sont de mauvais bateaux et que de nombreux “motor-boat” sont de piètres engins flottants. Dans la réalité, peu d'architectes et de constructeurs français se penchèrent sérieusement sur la formule fifty, pour la simple raison qu'en matière de bateaux de plaisance certaines conceptions, qui ne datent pas d'hier, conditionnèrent très fortement le marché : pour les uns c'est la valse des 18 pieds;, la Quarter Ton Cup, le rating vicieux, pour les autres la religion des cylindrées de 30 noeuds de moyenne, ou des 170 Km/h grâce au “power trim”, avec, et dans les deux sens, un dédain superbe, en prime, pour ceux d'en face.

Personne, à notre connaissance, n'a poussé la sincérité au point de dire bien clairement que dans une circumnavigation ou une navigation hauturière, en dehors des alisés ou des moussons, c'est à dire par les, routes buissonnières, on navigue rarement à la voile comme le voudraient la poésie, le romantisme bien compris ou 1' esprit sportif.

Pendant un tiers du parcours la navigation s'effectue ~ la voile pure, pendant un deuxième tiers, ou presque, elle s'effectue au moteur seul et par calme plat, enfin reste le dernier tiers où tout est possible et qui se négocie voile et moteur, moteur seul ou voiles seules selon le bateau, le temps dont on dispose, le temps qu il fait, les prévisions météorologiques, les vivres, L'eau douce, le tempérament du capitaine, la patience de l'équipage et l'importance des réservoirs de fuel. A quoi certains poseront la question : comment faisaient les grands voiliers du temps de la marine en bois ? Ils faisaient de préférence dans les routes à vents connus et réguliers, ils portaient un maximum de toile et embarquaient un équipage important pour les manoeuvres.

Ou alors ils trainaient dans des zones de calme plus ou moins longues. Et comme chacun sait le scorbut et les mutineries faisaient partie du folklore.

C'est pourquoi il convenait de donner du fifty' une définition nouvelle et réaliste. Pour nous le problème consistait à réaliser un fifty qui serait un trés honnête voilier hauturier et qui conserverait certaines des qualités d'un motor-boat, entre autres vitesse et autonomie.

Il nous était en effet apparu que ce mouton à cinq pattes était tout à fait réalisable compte tenu des progrès techniques de ces dernières années et qu'il serait en fait un 100 + 100.

LES BATEAUX BÂTARDS.

Pour des questions évidentes de volumes et de poids la limitation des stocks de combustible rend difficile de très longues traversées océaniques avec des motor-boat. De plus une panne de moteur qui serait irréparable en mer placerait le bateau et son équipage dans une situation extrêmement dangereuse.

C'est donc tout naturellement que d'aucuns affublèrent leur motor-boat d'une voilure d'appoint. Au mieux ces quelques mètres carrés de toile permettaient de se déhaler aux allures portantes en cas d'avarie de machine. Nous étions loin cependant d'un fifty convenable. De l'autre côté, certains propriétaires de voiliers habitables, après de nombreux séjours dans des calmes plats, ne serait-ce qu'en Méditerranée, cherchèrent à augmenter leur autonomie par l'adjonction d'un puissant moteur et de réservoirs de combustible.

Il y avait un long chemin à parcourir avant d'en arriver au jour' où un bateau serait tellement sur et confortable et aussi tellement rapide, que nous n'éprouverions plus aucun désir de revenir jamais à terre.

C'est ce bateau-là que nous appelons le bateau idéal. Il échappe aux calculs, au rating, aux ordinateurs, au R.0.R.C. au préjugés, à la mode, aux engouements, à l'intuition, au romantisme...

Le nombre des circumnavigateurs qui “continuent”, qui n'éprouvent aucun besoin ni désir de revenir è. leur point de départ terrien, qui poursuivent indéfiniment leur course à travers les mers et les vents, le soleil et les fies perdues, et les caps sans cesse recommencés, est connu. Et il est insignifiant.

De ce nombre minuscule il faut bien déduire qu'il n'y a, en définitive, que quelques très rares bateaux que l'on puisse considérer comme réussis. A ce niveau le bateau idéal prend allure de mythe.

C'est pourtant à partir de ces données que devait naître le Banjer. Aujourd'hui de nombreux propriétaires de Banjers vivent en permanence à leur bord et n'envisagent pas un retour en arrière. Le premier de la série porta 28 m2 de toile. Un Banjer, puis d'autres, portèrent ensuite 40 m2, puis 60 m² . aux allures portantes. Après quelques années de recherches, différents essais, de nombreuses améliorations et modifications, le plan de voilure fut finalement porté à près de 100 m2. avec bout dehors.

Le Banjer transocéanique était né.

C'est un magnifique voilier dont les performances s'alignent sur celles des meilleurs sans en avoir les inconvénients, ainsi que nous le verrons.

POURQUOI UN KETCH ?

En circumnavigation et à plus forte raison en navigation vacancière, l'intérêt de la voilure divisée n'a plus guère besoin d'être démontré. Il est possible qu'on perde quelques broutilles en vitesse théorique et sur une courte distance, mais le gain en sécurité, comme en confort, compense cette modeste perte au delà de toute espérance. Lorsqu'on navigue à deux, et d'autant plus lorsqu'on navigue seul, le problème du choix d'un gréement entre celui de ketch et celui de cotre, à bord d'un bateau de fort tonnage, ne peut se poser sérieusement.

Ainsi dans la navigation hauturière ou vacancière, en solitaire ou à deux, la rotation des quarts diurnes et nocturnes auxquels il faut ajouter les différentes obligations du bord, entraînent parfois un état de fatigue assez peu compatible avec les manoeuvres, par gros temps, d'une grand'voile de 55 mètres carrés ou davantage, ou d'un génois de 80 mètres. Surtout pour les plaisanciers d'un certain âge.'

C'est pourquoi nous avons étudié, réalisé puis essayé différents `plans de voilure avant de nous arrêter aux deux plans actuels, respectivement 62m2 et 97m2 aux allures portantes, avec foc, trinquette, grand'voile, voile d'étai et artimon. La plus grande voiel, le génois ne dépassant pas 43m².

Le Banjer

FICHE TECHNIQUE

Dimensions

Longueur HT...... 11,13 m.

Largeur .............. 3,48 m.

Tirant d'eau ...... 1,40 m.

Lest ,.................... 4 Tonnes

Déplacement .... 12,2 Tonnes

Jaugé brute .... 14,30 Tx.

Jauge nette .... 9,29 Tx.

Réservoirs de fuel : 1.500 litres.

Autonomie moteur . 1.000 milles.

Réservoirs d'eau douce . 750 litres.

Réservoir d'eau usées . 110 litres.

Moteur Perkins 4 cyl. 62 CV è. 2250 t/m.

Inverseur hydraulique Paragon réduction 3 : 1

Réfrigération par double circuit (eau douce et eau de mer)

Montage sur silent-blocs - compartiment insonorisé.

Commande Morse - Paliers en caoutchouc lubrifiés par circulation d'eau forcée,

Hélice 3 pales, en bronze, diamètre 710 mm.

BANJER 37 MAIN (SIMPLE) PARAMETERS

Main Data input

LOA : 37'

Lwl: 31.17'

Beam: 11.42'

Bwl : 9.84'

Draft: 4.43'

Displacement: 27778 pounds

Sail Area : 301, 450 & 807 sq feet

(28, 42 & 75 sqm)

|

Displacement / Lwl = 409.5 (Banjers are really heavy-weights!)

Displacement to LWL: A medium value would be 200. 300 would be high (Heavy Cruising Boat) and 100 would be low (Ultra Light Displacement-ULDB). Boats with low numbers are probably uncomfortable and difficult to sail.

Hull speed = 7.48 knots as by static waterline lenght calculation. Tested aboard is around 8.5 knots.

Hull Speed: This is the maximum speed of a displacement hull. Some racers and lighter boats are able to achieve greater speed by lifting over the bow wave and riding on top of the water,that is, planing.

Sail area / Displacement = 5. 25 (28 sqm) ; 7.88 (42 sqm) & 14.08 (75 sqm)

Sail Area to Displacement: The sail area is the total of the main sail and the area of the front triangle. A racing boat typically has large sail area and low displacement. A number less than 13 most probably indicates that the boat is a motorsailer. High performance boats would be around 18 or higher.

Lwl / Beam = 2.73

LWL to Beam: A medium value would be 2.7 ; 3.0 would be high and 2.3 would be low

Motion Comfort ratio = 61.57

Motion Comfort: Range will be from 5 to 60+ with a Whitby 42 at the mid 30's. The higher the number the more comfort in a sea. This figure of merit was developed by the Yacht designer Ted Brewer and is meant to compare the motion comfort of boats of similar size and types.

Capsize ratio = 1.30

Capsize Ratio: A value less than 2 is considered to be relatively good; the boat should be relatively safe in bad conditions. The higher the number above 2 the more vulnerable the boat. This is just a rough figure of merit and controversial as to its use.